Life was getting dull in Tbilisi, so yesterday I went to see Chechnia. Now that I have your attention I can admit that I didn't actually go to Chechnia, but Roger Clemens could have thrown a stone to Chechnia from where I was standing. I got together a group to go with a travel agent to Shatili, a remarkable village built many centuries ago in the mountains three miles from the Chechen border. It consists of a complex of four and five story houses, all overlapping and interlocking on the side of a hill, so that you can walk from the third floor of one tower to the first floor of its neighbor.

Ten of us left Tbilisi after work on Friday. More than half of the group were American USAID/Barents advisors to the tax department. One young British guy has started an English language magazine that lists and reviews Tbilisi events and restaurants. There were about three guides plus two interpreters to look after us. We drove north from Tbilisi for about an hour on the Georgia Military Road. Then we turned onto a smaller paved road following the eastern branch of the Aragvi River. They call this branch the Black Aragvi and it really is black. There is lots of shale and the rushing water picks it up.

Half an hour up the Black Aragvi valley we stopped at a clearing by the river for a picnic supper. There was a spring that had been fixed up very nicely and the water tasted good. Our guides built a big fire and started chopping tomatoes, cucumbers, scallions and onions. When the fire had burned down to coals they cooked shishkebab (pork and beef). Of course there was lots of fresh bread and cheese. Then they pulled out a five gallon gas can that was filled with wine. Not bad!

Dinner lasted for a while and it was late by the time we arrived in Barisakho. Our host there wanted us to eat again. We all said we had just finished dinner, but they insisted that we eat something. It would have been rude to refuse, so we ate khachapuri (cheese pastry), bread, cheese and vegetables and had some more wine.

|

| Barisakho |

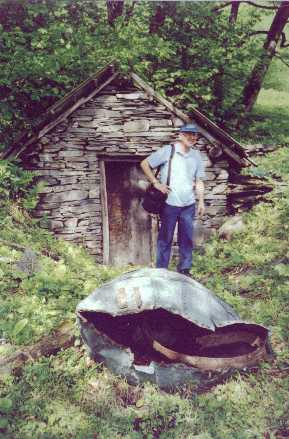

One of our guides was born in Barisakho and she has many relatives here, so after breakfast she told us to follow her up the hill overlooking the village. The dirt road was too steep for cars, but there were several houses further up. After twenty minutes of steady up-hill walking she met a cousin who would show us a holy place. He had the responsibility this year to look after it. He explained (through the interpreter) that this was a place where once or twice a year the men of the village gathered for a ceremony plus food and drink. Women were not allowed to go there. The holy place looked like a small stone shed and I still donít understand what made this place so holy, but the people of Barisakho have been using it for thousands of years, starting well before Christ. The young man obviously took his responsibility seriously.

|

| Barisakho Potato Fields |

Barisakho is at the bottom of a steep valley and is very green. Many of the people here raise sheep. In the summer they take many of the sheep up in the mountains and cut the grass here for hay to feed them in the winter. We saw many old women tending gardens. The main crop seemed to be potatoes. The village had one or two small shops where you could buy cigarettes and essential groceries and a gas station selling gas ("petrol") in twenty gallon cans.

Shortly before Noon we piled into the van and headed for Shatili. Barisakho was the last village large enough to have a place where you could buy anything. Soon we saw a sign saying that busses were not permitted past this point. The pavement ended and the road started up to the mountain pass. We stopped for lunch at a bridge next to a waterfall. Our guides prepared a meal very much like our dinner on Friday.

|

|

| Barisakho Holy Place | Guardian of Barisakho Holy Place and His Cousin, our interpreter |

|

| Lunch Break |

Further along we came to the beginnings of three tunnels, right next to each other. We later learned that the Soviets had started construction of a railroad tunnel to connect Tbilisi directly with Russia. The first attempt failed and they tried a second time. The third tunnel might have been for construction purposes. They had built a large apartment complex for the workers and done preparatory work for the railroad between here and Tbilisi. If they had succeeded this may have been one of the longest tunnels in the world, at least thirty miles. But they didnít.

There were beautiful views from the top of the pass. From here the going was very slow. Our guide explained that the road had only been opened for the summer the previous week. Snow blocks it for seven months out of the year. We had to drive through numerous streams that crossed the road. Several times we all got out of the van to make it easier for the driver to get through the stream. Then we got to a place where the real road was still blocked by ice and snow that had slid down the mountain. The only way to go ahead was to drive a hundred yards though the river. We were skeptical, but then another car arrived and they plowed through successfully. We all walked around and let our driver get the van through.

|

| Near the Top of the Pass to Shatili |

|

| The Driver Made us Get Out so that the Van Could Cross the Stream |

Then we arrived in Shatili.

|

| Shatili |

In 1953 Stalin "convinced" all twenty families living there to move to suburban Tbilisi. Twenty years later they built a road so that you could drive there, at least during the five months out of the year that snow did not block the pass. Then in the early 1980's they built a dozen new houses a couple hundred yards from the old village and let the original inhabitants move back. A retired doctor who was born in the old village showed us the house he was born in and lived until he was eleven. He is trying to raise money to protect the old village as a museum.

|

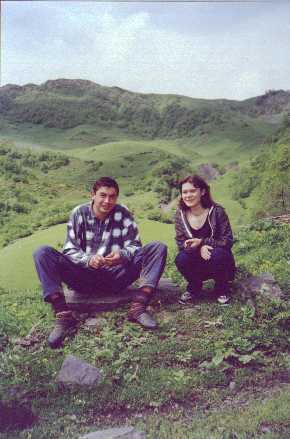

| Chechnia |

Shatili has a small hydro plant to generate their own electricity and everyone appears to make a living by keeping cows and making cheese. I don't know how they sell it because it takes three and a half hours to drive to the nearest village big enough to have a store. The government does offer helicopter rides to Tbilisi periodically and last month they installed a satellite dish so that the residents can watch television.

There are also a dozen Georgian Border Guards living next to the village. They don't feel a need to guard the border too carefully, because there is no road on the Chechen side. We did meet two Chechens who said that they would hike three hours to the nearest road in Chechnia. Our guide said that the Georgian government doesn't mind as long as they are not carrying guns back and forth. So we went to the trail head and then up to a point above the river that is the boundary lines. We walked past the empty guardhouse and our guide said that often there is a border guard or two inside, but not today. Then we waved to our Chechen friends across the river as they walked home. (They said that one of them would come back the next day on horseback with some petrol for his Georgian friends who had driven him to the border. They had punctured the gas tank of their car and it was a three and a half hour drive to the nearest gas station. So it would be much quicker to bring some over from Chechnia on a horse!)

It's beautiful country though I can't imagine living with such isolation