Svanetti Ė July 1999

Tuesday, July 13 was my last day of work. I had many errands to do on Wednesday before I could start my week-long vacation in the Caucasus Mountains of the Svanetti region. My landlord, Khaki agreed to purchase my car and he helped me get some minor repairs completed before the trip. They took much longer than we planned and in the end I did not leave Tbilisi until after dinner. It was midnight when I arrived in Kutaisi so I was relieved that I was returning to Laliís guest house there where I had been several times. Lali and her husband made me feel very welcome.

Thursday morning I got a prompt start on my way to Mestia, the capital of the Svanetti region. I made a wrong turn trying to get out of Kutaisi but before I long I was headed west on the highway to Zugdidi. There are three roadblocks manned by Russian peace keeping troops on the outskirts of Zugdidi because that is the only real crossing point between the break away province of Abkhazia and the rest of Georgia. Last year when I got to the roadblocks they asked me for cigarettes, checked my passport carefully and looked in the back of the car to make sure I wasnít carrying any guns. This year I rolled down the window, handed them a pack of cigarettes and happily drove on my way.

|

| To Remember |

The road from Zugdidi to Mestia is paved but not as smooth as the highway from Tbilisi, so the going is slower. It follows the Inguri River the whole way, often rising high above the river. By the side of the road I saw what looked like bird houses with bottles of wine in them. They are actually memorials to people who died on the road. The idea is that if you know the deceased you will stop and drink a toast in remembrance. Some of the memorials even have a table and benches to make it easier. Iím not sure that drivers on this road should be drinking toasts to anyone, but the idea of stopping to remember has some attraction.

I was still a couple hours short of Mestia when I stopped for three Czech hitch-hikers. I had my bicycle in the back seat and they had too much luggage for the three of them to fit into my car. They didnít know when they might get a bus ride, but they didnít seem too worried.

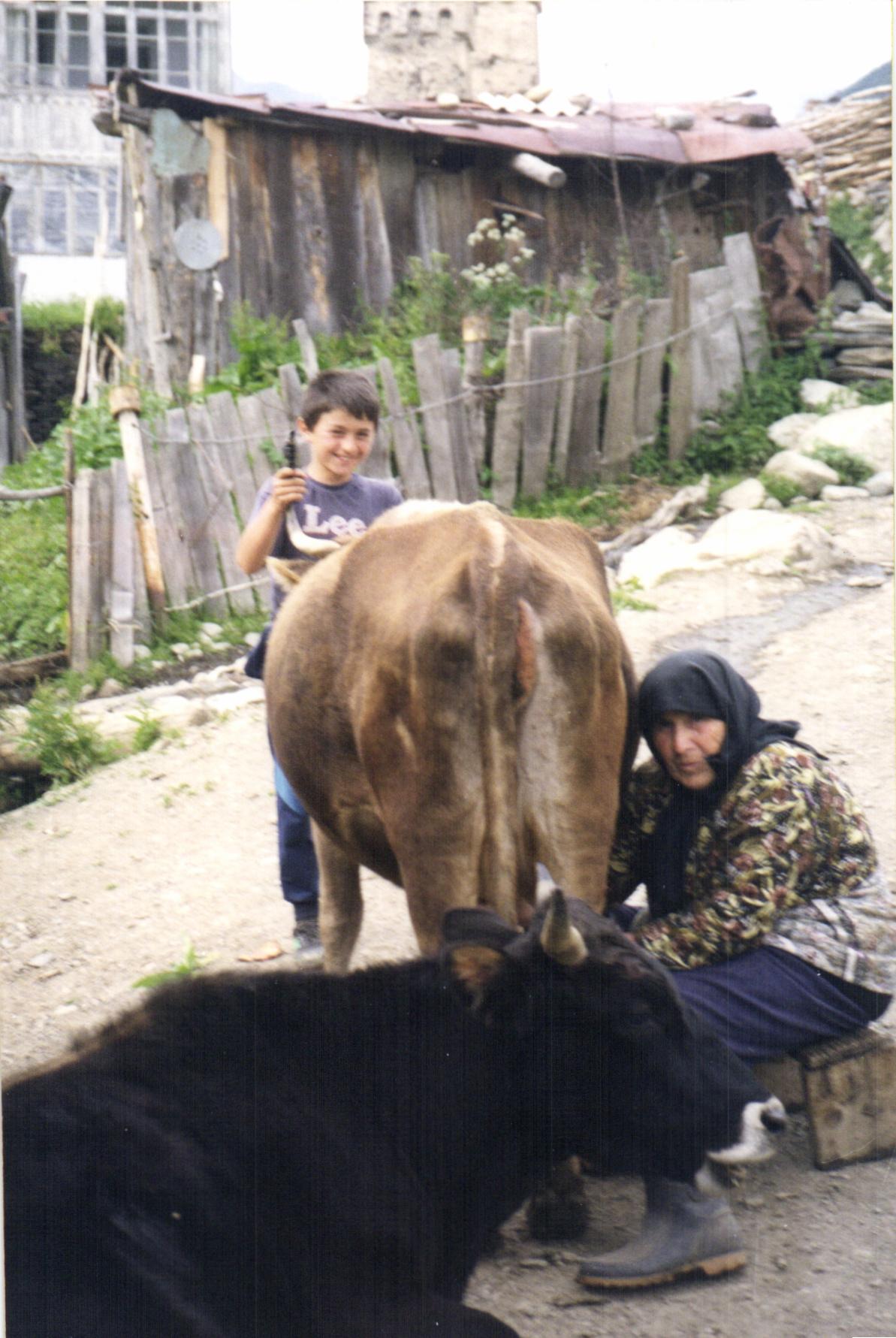

I arrived in Mestia in the middle of the afternoon and greeted my hostess Nana and her twelve year old son Giorgi who was my guide. Giorgi borrowed a bicycle from his younger cousin and we rode around Mestia. We stopped at two mineral water springs. I liked the one that was carbonated while the other tasted too salty for me. I met an American photographer named Andrea who was staying in Nanaís sisterís house right next door. We went to a house where a group of Mestian men were practicing their singing of traditional Svanetti songs. They had finished a big meal but the women quickly brought us plenty of food.

In the evening a bus arrived with the Czech hitch-hikers. Their plan was to camp out in the woods, but somehow Nana convinced them to stay in her hotel. Iím sure she charged them less than she was charging me because they didnít have that much money. At dinner I learned that they were students who were traveling around Russia and Georgia. They had entered Georgia without visas by coming through the break-away province of South Ossetia. Now the were looking for a place to cross the border back into Russia where they could get out without visas (in Georgia and all the former Soviet Union the border guards check you just as carefully when you are trying to leave as when you arrive). There are no roads that connect Russia to this part of Georgia but you can hike ten or fifteen miles over the high mountain passes, going well above the snow line. There are border guards on the Georgian side, but they donít seem to be overly bureaucratic. Nana said she would talk to some people and find out what would be their best plan. I guess it worked, because they didnít return!

The next day I headed off to Ushguli with Andrea and Giorgi. Ushguli is less than thirty miles away, but the drive takes more than two hours because of the poor quality of the road. But it is a spectacular drive over mountain passes, through several villages and following roaring rivers. Ushguli claims to be the highest village in Europe where people live year-round. It is also famous for its towers. Throughout Svanetti many houses have towers adjoining them. Families would go there to defend themselves from hostile neighbors or invaders. In Ushguli almost every house has its own tower.

We arrived late in the morning and Giorgi greeted his cousins and showed us their house where we would stay. They were very proud to show off the hot water they had installed, complete with showers. They said that this was not the only hot water tank in Ushguli but that it was probably the only tile shower room. The outhouse was still the only toilet. We explored the village while the boys joined a soccer game on one of the roughest soccer fields I have ever seen.

After lunch we decided to climb the hill to see the ruins of what may have been Queen Tarmaraís summer palace. Two of Giorgiís cousins (Levani and Richard) came with us. We climbed steeply through the woods for about an hour, pausing to taste berries and other plants. Little remains of the palace except for the fortress wall and a tower but there is still a beautiful view. On the other side of the hill there was a beautiful meadow covered with wild flowers. We collected some of them for Levaniís mother.

|

| Summer Palace |

|

| Wildflowers |

Meals in Ushguli are simpler than in other parts of Georgia. Potatoes seem to be the only vegetable that grows here and are a staple of the diet. They have lots of cows so the other staples are cheese and yogurt. As in all of Georgia there is always khachapuri (cheese pastry). Though they raise pigs and chickens, they only occasionally eat meat. There are no grapes for wine so vodka is the drink of choice.

The next day we decided to hike to the bottom of the glacier that is the source of the Inguri River. I had visited this same glacier last year but had only seen it from the bottom. I explained that this year I wanted to walk on it, to see what it was really like. They thought I was a bit crazy but they agreed. Four of Giorgiís cousins decided to come on this expedition. The boys all had horses while Andrea and I were much happier walking. After a couple hours we came to a spring of mineral water that was quite good. One of the boys had brought a 10-liter jug so that they could take some mineral water home. They filled the jug and stashed it on the edge of the river while we ate our lunch. I shared some peanut butter and Ritz crackers and some Oreo cookies. They had never had peanut butter before and were quite curious.

|

| On the Way to the Glacier |

Soon the trail got rough and the boys had to leave the horses behind. We started climbing over many boulders as we circled around, trying to get on top of the glacier. The ground by the glacier was composed of piles of loose rocks and the footing was treacherous. It was also very steep so the boys had fun throwing rocks down and starting avalanches. We made it up onto the glacier though it looked much nicer from the bottom. The snow on top had melted a bit so that there was more rock than snow. And it looked dirty. We looked up the mountain and realized that this pile of ice, snow and rock had started way up the mountain a long time ago and so that it had plenty of time to collect rocks and dirt on its way down. This probably wasnít my safest expedition but it was fun.

|

|

| Near the Glacier | Holding on Tight |

When we got back to the horses we finished off our lunch food and headed back to the mineral water spring. The jug of water was nowhere to be seen. One of the boys dunked himself in the freezing water (we were only a mile or two below the glacial source) to make sure that it was not at the bottom of the pool where they had left it. I started walking back while they searched the river. They did find the jug about 250 meters downstream. By now it was getting late and Irakli was overdue for retrieving the cows from their pasture. So I agreed to ride on the back of Giorgiís horse as we headed home. I was nervous but he controlled the horse well.

Andrea had gone back earlier to take some pictures in the village. She was most upset that so many of the children wore shirts that said "Adidas" or "Chicago Bulls". It didnít matter to her that the shirts were counterfeits, she thought they still ruined her pictures.

When we got back to the village we discovered that a group of six French tourists had arrived. There are no telephones here, so nobody ever knows when to expect visitors. In their honor we had a slightly fancier dinner than usual.

|

| Firewood for the Cookstove |

I am still confused by the extended family that was living in

this house. Giorgi calls everyone a cousin but he had to stop and

think to explain the exact relationship of some. The oldest woman

was his grandfatherís sister. I think her daughter was Levaniís

mother. Irakli and his brother live in a different part of Georgia

but spend their summers here. Another old woman might not have

been related to the family at all. In any event, the women seemed

to stay home to bake bread, make cheese and do other cooking and

washing during the day while the men and oldest boys went to

distant fields to look after the cattle and cut hay. Giorgi was

the only one in the group who spoke English and my very limited

Georgian kept our conversations at a very simple level.

Giorgi explained to me that there were no shops or even kiosks in Ushguli. A couple times a week (but not on a predictable schedule) someone would drive a truck six hours from Zugdidi. The women of the village would grab any cheese they had made and swarm around the truck to see what goodies were available. The driver would trade whatever he had brought for cheese which he would take back to sell in Zugdidi. Of course this could only happen during the half year when the road is not covered with snow. In the winter the only way to communicate with the rest of the country is to walk or ride a horse the thirty miles to Mestia.

The next morning we went to an "Ethnographic Museum". It was actually a collection of wood carvings that the proprietor had made himself. It took him six months to carve one chair. They were probably for sale, but he didnít seem to be trying to sell anything and I didnít ask. Then we drove back to Mestia, giving a ride to two more of Giorgiís cousins, one a very young mother with her baby. They lived fifty kilometers the other side of Mestia and had been visiting relatives in Ushguli for a couple weeks. Nobody seemed very worried about schedules or how long they would stay before getting a ride home. We stopped for lunch by a small lake. Though we were at a high elevation the forest here was thick which is unusual for Georgia mountains.

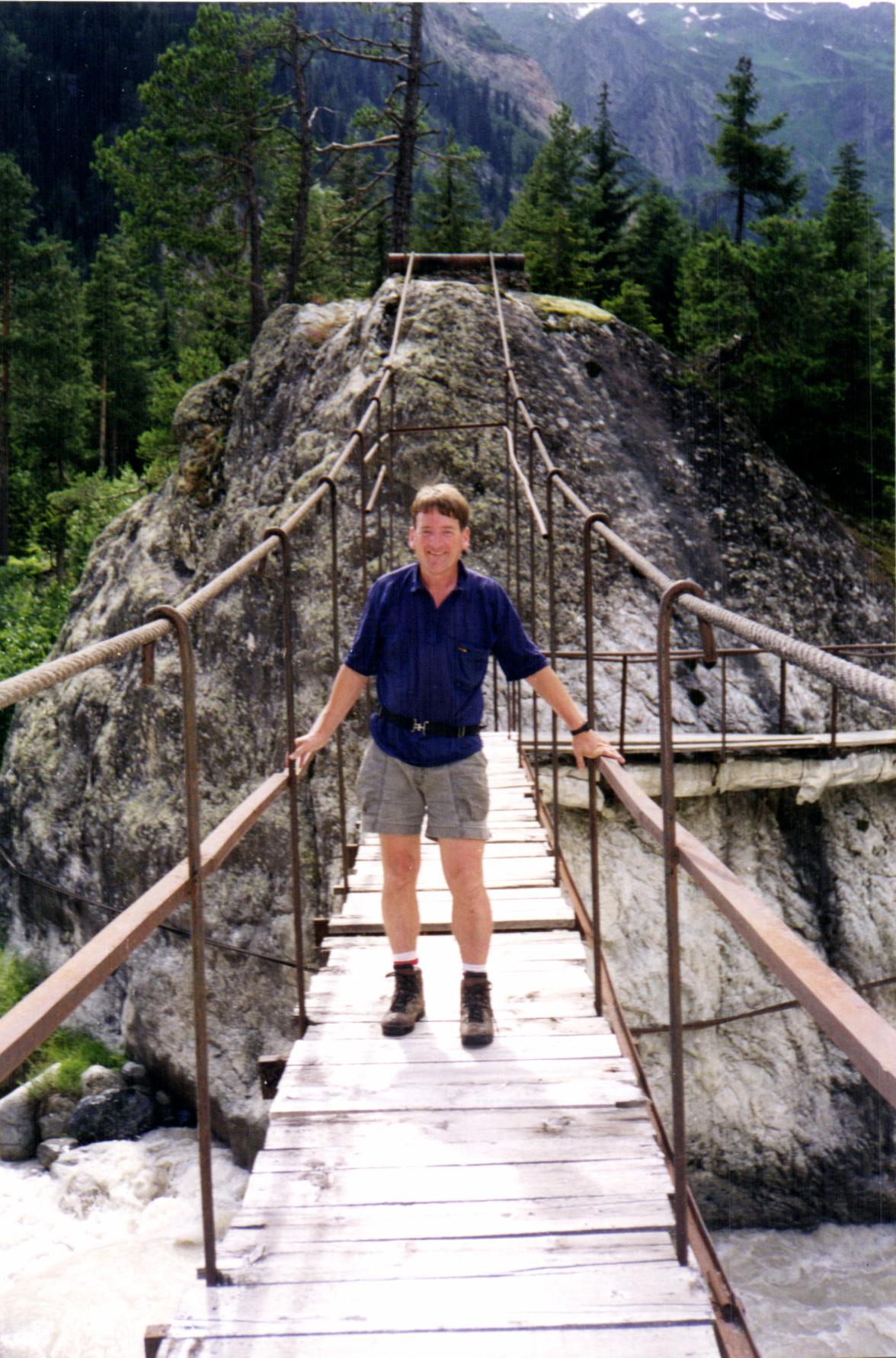

The next day Giorgi was not feeling well so I explored Mestia with my bicycle on my own. I followed one dirt road next to a river for many miles beyond where cars could drive until I came to a sturdy suspension bridge. I could see a glacier not too far ahead, but distances are hard to judge and it was getting late so I headed back. But by then my hosts were already worried and were driving all over Mestia searching for me. Georgians are very protective of their guests.

|

|

| A Long Way Down | Looking up toward the Russian Border |

The next day Giorgi was feeling better and we decided to go find this glacier. He had never been there but agreed that it would be a fine destination. We got a ride part way up, then got on our bicycles to continue up (me on my mountain bike, Giorgi on his cousinís small single speed bike). We bicycled as far as the suspension bridge. Today we found Georgian border guards there. Giorgi greeted them. He didnít seem to know them personally but everyone knew everyone elseís families. They wrote our names down in their book and gave us directions.

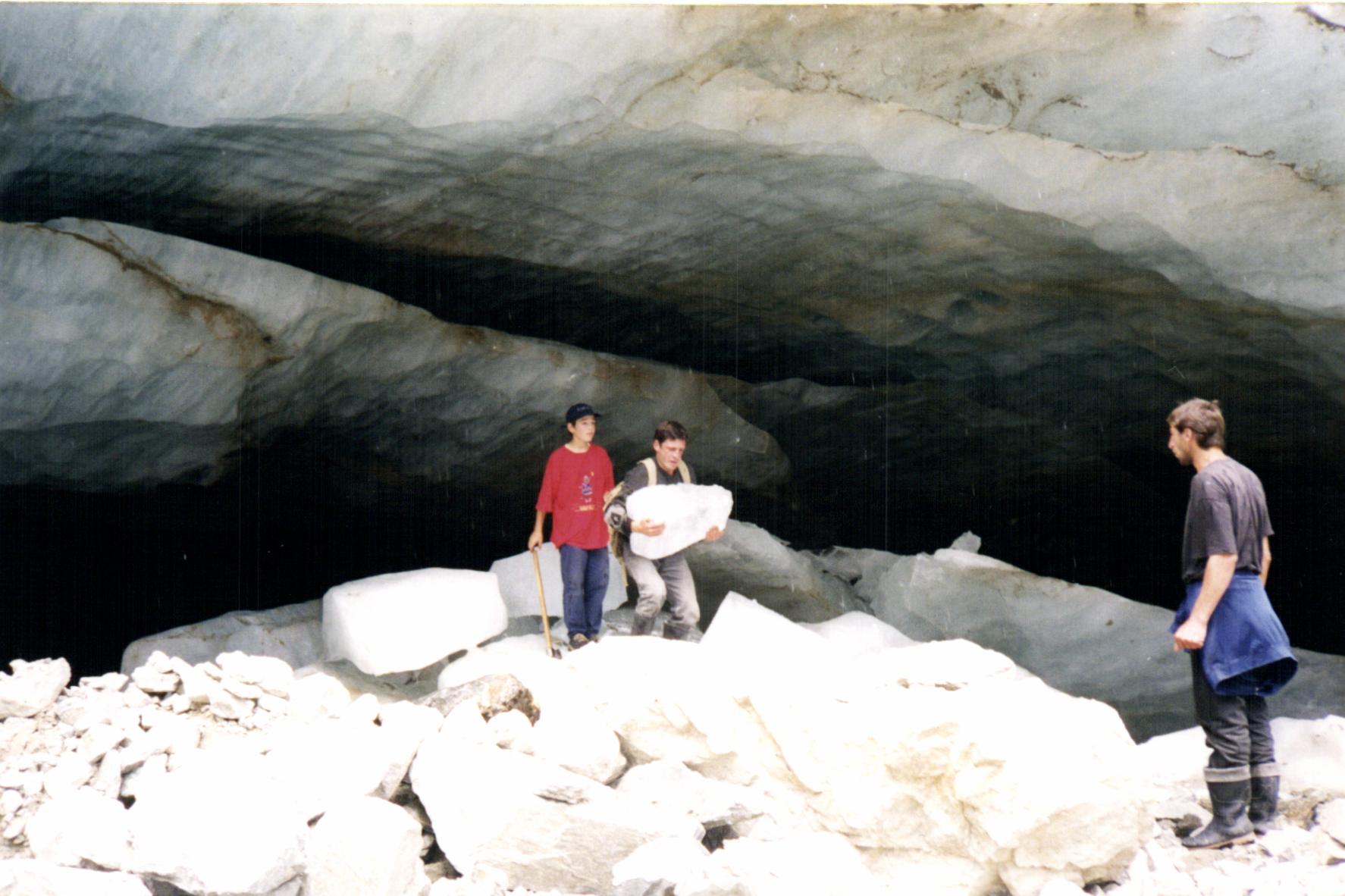

An hour or so up the trail we got to the bottom of the glacier. It towered over us with rocks and ice occasionally crashing down. Just as we arrived we were joined by four men with backpacks. They cut big blocks of ice and strapped them to the backpacks. They explained that someone in Mestia had died and they needed ice to preserve the body for a few days.

|

|

| Cutting Ice Blocks at the Glacier | Border Guard Picking Wild Strawberries |

On the way back we found thousands of tasty but tiny wild strawberries.

|

| Lunch with Border Guards |

The bike ride down was much easier than the ride up the hill! But we were late enough that another search party was looking for us. Back in Mestia Giorgi and a cousin picked several liters of delicious sweet cherries from a huge tree.

After dinner Giorgi asked if I would be willing to sell my bike. He said that in Georgia it is difficult to find a good bike. He had been saving his money to buy a horse but he had been impressed by the mountain bike. He is obviously much better off than most Georgians because his mother seems to arrange much of the travel to the region and he works regularly as a guide for foreigners, but it was still a major purchase for him. Since I was going home to the US in a few days I agreed to a bargain sale.

The next morning, Wednesday, I drove with Andrea back to Kutaisi. But first I had to listen to her fret about money. She had made no advance arrangements about how much to pay for room and board and in the end she paid a total of $20 to her host for four nights and three meals a day. I guess she is not making any money while she is here taking pictures but it seems wrong to take advantage of the Georgians this way. I paid $30 per night plus $10 a day for my guide. We broke up the six hour drive by stopping at a restaurant east of Zugdidi. We were their only customers but they produced a fine and inexpensive lunch. Andrea didnít want to pay $30 to stay in Kutaisi so I dropped her off at the bus station where she quickly found a van (marshsutka) that would taker her non-stop to Tbilisi.

I went to my old friend Laliís house Ė this was my seventh night in her little hotel. For dinner she invited her son-in-law Gogita and his nephew Irakli who had been my guides on my first visit. They greeted me like an old friend. Gogita looked under my car and noted that one of the shock absorbers was broken. So in the morning he bought a new one and installed it for me and charged me $20.

I had to be back to Tbilisi by Thursday evening because my landlords were having a big birthday party for their sixteen year old son David. Several aunts and uncles were visiting from Israel and New York and Khaki wanted a good Georgian party. There were at least fifteen of us having dinner under a shelter in the courtyard of the restaurant with a band performing just for us. Like most Georgian parties the food was excellent, there was plenty of wine and the toasts seemed endless. David had only one friend his own age at the party, a cousin visiting from Moscow. I think the two of them would have preferred a hamburger at MacDonalds! Near the end of the party two recent retirees from the army came and asked for a drink. Georgians have sympathy for their soldiers because their salaries are minimal and usually late and their food and living conditions are often very poor. So everyone felt obliged to be generous. Anyway there was plenty of leftover food and drink!